The Editorial

Interview with Loubna Bensalah

by Janiki Cingoli, President of Italian Center for Peace in the Middle East

Publication date: November 30, 2018

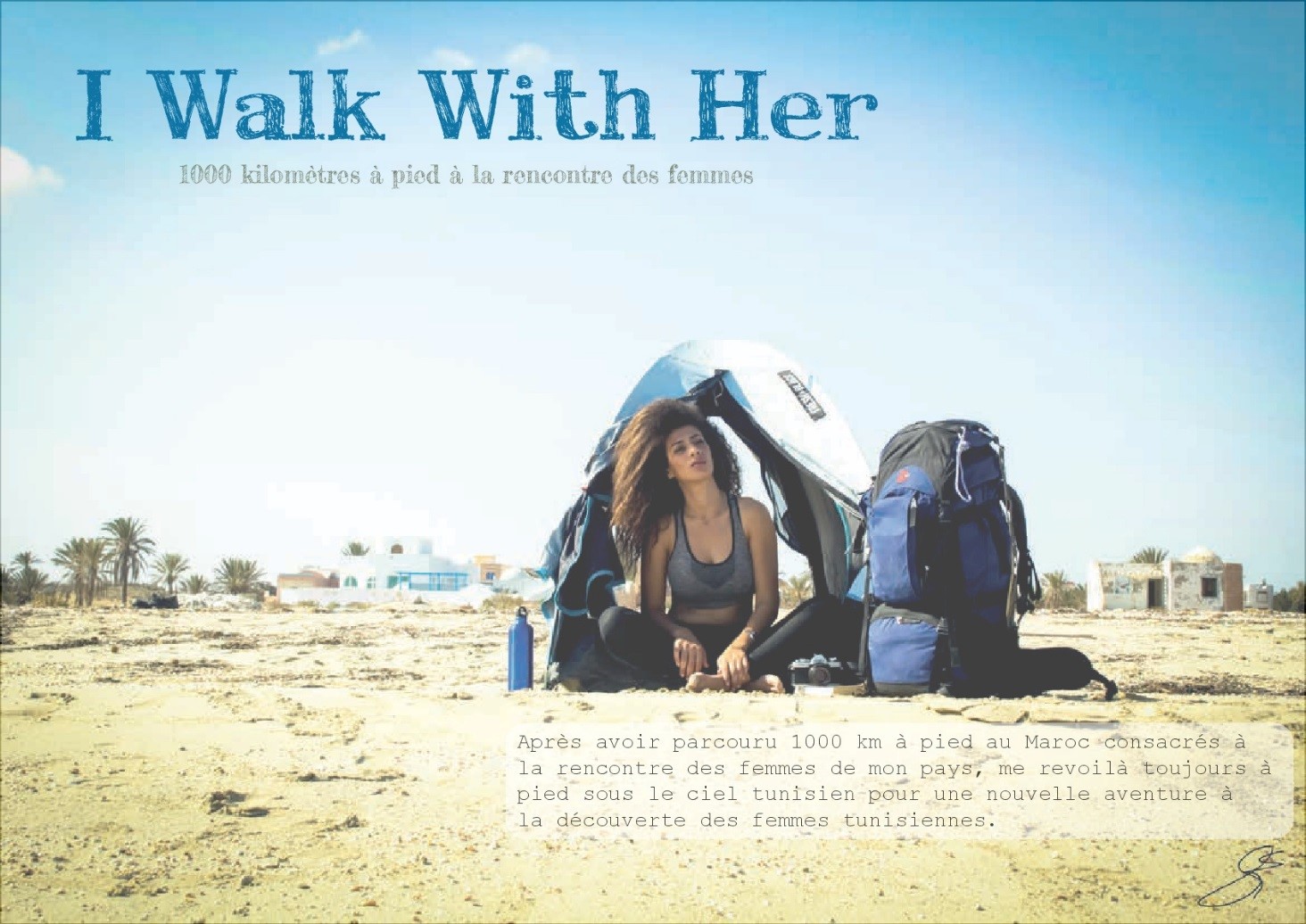

In 2016, the then 20-year-old Loubna Bensalah, a young Moroccan activist famous worldwide, walked for 1000 km in Morocco to know herself and meet other Moroccan women – starting her project called “I Walk with Her”. In 2017, Loubna marched for 100 km in Tunisia, meeting groups of women in small rural villages. She was awarded by UNESCO in Paris, on 22nd April 2018. She has been professor of communication at the Mohammed V University of Rabat.

In 2018, her marches became a project called “Kayna – conquering the public space by women’s march”: a series of meetings dedicated to women, where they could walk, stop, discuss, and, above all, symbolically “occupy” places usually reserved to men, such as beaches.

These days, Loubna is in Italy to tell her story. I have had the pleasure of accompanying her for two days, on the occasion of the two events organized by CIPMO (in Milan and Turin respectively). Seldom have I met such a creative, innovative, prestigious and significant woman as her, so I have not missed the chance of interviewing her, also touching upon less-known aspects of her life experience – given the positive relationship that we had established between us.

Loubna, you travelled in Morocco and Tunisia exclusively on foot, starting with your 1000-km-long walk in Morocco: were you not afraid of being robbed or assaulted? I did know personally a young artist, Giuseppina Pasqualino, who had done something similar in Turkey, dressed in a bridal gown: I strongly advised her not to do so. Unfortunately, she was found dead in the fields: she had been raped and brutally killed. This is why I am asking you if you have ever had fear.

To be honest, no. Actually, many people told me that I was crazy, and that what I was doing was very dangerous, but once I had taken my decision, all I wanted was to leave, without considering anything else. Maybe I was wrong, but in my first walk across Morocco I trusted my fellow countrymen. I have been brought up valuing hospitality and self-giving, and I have always believed that nothing bad could stem from our culture.

However, you told me that, beside the hospitality factor, there is a violent component among Moroccan men. Therefore, if a woman goes out on her own, she may be victim of violence.

It could be, but this was a risk that I had not bargained for. Honestly, if we based ourselves on the violent comments we see on social networks, we would come to the conclusion that Morocco, and other countries as well, is a violent country. This is not what I have seen while walking there. People were really hospitable and open: they all wanted me to stay at their place, to eat a meal with them, to stay for the night. They lived in small rural villages and had no connection with the social media, but welcoming the stranger is definitely something engrained in their culture. During my walk in Morocco, I travelled along the Atlantic coast, where there live people used to meeting tourists and beach-goers living next to them.

However, I do believe that violence is on the rise. If I had to set out for my 1000-km walk right now, I would think twice before doing it.

Could you better explain me the process that led you to make this decision? I mean, what happened in the depth of your soul? What mental process did you engage in? I do not think that you made such a decision on a whim.

Since I was a child, I have always dreamt of exploring, seeking, travelling. With the passing of time, these ideas faded away: in my homeland I tried to “seek”, but what I actually did was “researched”, more than anything. Why in my homeland, though, and why women? Because this makes thinks more interesting.

When I left my family environment and faced the rest of society alone, I started living on my own: it was only then that I fully realized that there was no equality between men and women. I sensed it day after day: on the job I did not have the right to speak, listen, or discuss, or to be active in politics, to do something in my society, just because I was a woman – and therefore I lacked any analytical skills. Such episodes kept increasing in number. Apparently, a woman is not capable of analysing this kind of problems: a woman is not supposed to read, her sole concern should be cooking or taking care of her hair.

Clearly, those were not my priorities: mine were Moroccan society, what happened within it, etc. Thus, I often ended up being the only girl among lots of men, boys, and (male) classmates discussing Moroccan policy and talking about what happened in my country, or even about football. For example, I was among the few girls talking about 20th February and the Arab Spring; I was one of the few that tried and wanted to know, understand, analyse.

I was sick and tired of that world, so I decided to leave, especially because of the condition of women. I completely rejected that society, because I could not find a place in it as an individual, as a woman, as a young. I no longer had faith in politics and society, I felt revulsion from them. I kept telling myself: “This is not Morocco. It can’t be”. The Morocco I had to face every day was not the Morocco I wanted.

But you belong to a bourgeois, wealthy family, don’t you?

Let’s say my family is an ordinary, modest, middle-class one, although we used to live a little bit better than the average.

You said that you had not faced any dangerous situations…

Actually, I haven’t said I didn’t face any dangerous situations. I was not afraid of running risks, but this does not mean I haven’t run any!

You recalled that episode when the police stopped you and two friends of yours while walking at night. If I remember well, your reaction in that circumstance was hard, correct?

You are right, but that happened in my ordinary life, not while I was walking across Morocco. It was October, and I was eating out with two (female) friends of mine at a Syrian restaurant in Rabat, Yamal Acham. We finished eating and went out at around 11 pm, there was nobody to be seen but for two guys in a car who were following us. They tried to approach us, but a police car saw them and made those men run away.

However, the police officers came back to us and asked what those men wanted from us; we answered – perhaps naively – that they had tried to assault us, as it often is the case in our country. One officer replied:” Well, that’s normal. What do you expect them to do, if they see three young women walking on the street, one of which is also smoking a cigarette? What are you exactly looking for?”. My reply as 21-year-old young woman was: “Excuse me, there is no place in Morocco where a woman is not allowed to walk at 11 pm, nor a place where she is not allowed to smoke a cigarette. On the contrary, there is a law against sexual assault. So, you should not be here telling us how to behave, but you should be pursuing those two guys, stopping them and asking them what they wanted from us. All we wanted to do was to eat out at a restaurant in peace and tranquillity”. But, after all, is was just an isolated case.

In Tunisia, however, you could have found me at a police station every 48 hours, especially when I was crossing the north-eastern regions. Sometimes I was accused of stealing archaeological finds, some other times of spying on behalf of Morocco or the Mossad (since there is a large Jewish community in Morocco). I heard the most nonsensical and stupid accusations: nobody seemed to be able to understand why a woman would march from village to village on her own, sleeping with the locals.

You often talk about the gap between law and practice. In Morocco, there are laws on sexual assault and on succession, but – as you explained – people do not know these lows, and therefore people’s mentality is different. If one asks for these laws to be enforced, s/he would be looked at as if s/he were coming from Mars!

The problem in my country (or regime, or whatever it is) lies in the mentality, at least when it comes to gender issues. Law have been passed, but the people’s mentality goes in the opposite direction. First of all, laws are voted and passed by the Parliament, but they are far from common people, who are and remain unaware of these laws. Secondly, people do not feel represented in these laws, as feminism is generally rejected. Thirdly, people are not ready for such a radical change: you cannot impose overnight a set of laws developed in Europe to Moroccan men and women.

We are lucky that these laws are in force, and personally I am in favour of change, but I believe that it is more important to change mentality rather than laws. New mechanisms and procedures must be devised and adopted in order to make these laws be fully understood, absorbed and accepted by the people. We shouldn’t make them feel forced to do things they disagree on. It I essential to explain people the process and the reasons behind the laws, otherwise such laws will never be actually enforced.

Do you think your work has, to some extent, changed women’s mentality in Morocco?

I do believe that my work, together with that of many communities and organizations for the promotion of women’s role (especially after the MeToo movement), has had and will continue to have an impact. There is a Moroccan proverb that “a hand alone cannot applaud, you need two of them”. I find it particularly appropriate, since I cannot change the world alone, nor can an organization, nor civil society alone. We need the Moroccan government to listen to civil society and to make efforts to change this situation. We need communication and more women in the government, but not as undersecretaries or spokespersons of whom we can say “Hey, look, there’s also a woman in the collective photo”. I want women that are actually part of the government, women with real power.

You certainly must have met a huge number of people along you route, which is indeed a fundamental part of your work and your experience as a human being. What is the most important and moving moment of this experience?

There have been several, and at different levels as well. Usually, when I first arrive in a village, I am regarded by local women as a sort of “priest”, in the sense that they come up to me and tell me everything they want, because they know that I will not judge them. In their eyes, I am “the emancipated woman”.

If I have to talk about a woman who really shocked me – I don’t know exactly how or why – I would choose a young woman from a tiny Moroccan village. Her husband had invited me over for dinner: he must have been 35, while she was definitely younger, probably 24 or 25, and had already had two children, each of whom was around 5 or 6 years old. I immediately asked myself at what age she had got married, so I actually asked her why she had got married so early and had already had two children. We spent hours talking about her youth.

Once completed her studies, she wanted to become a painter and illustrator, but she had no means. Then she fell in love with a man and stayed with him for 4 years; however, the very same man with whom she had “a complete relationship” (in all senses of the word) left her and married another woman. She thus found herself alone and no longer virgin (in our culture, virginity is absolutely essential for a 18 or 19-year-old girl).

She went through a lot of sufferings, she didn’t know that to do, but luckily a man asked her family the girl’s hand in marriage. Needless to say, her family was very happy, also because they all considered the suitor very understanding – particularly regarding the girl’s (lost) virginity.

However, the young woman had had her virginity restored with expensive surgery. I asked her how she had been able to afford it, given her dire economic condition, and she answered that it was her suitor who paid for it. I was perplexed, so she went on explaining that it is always the husband who gives his wife the money for buying a table, a bed, or whatever they need to furnish their new house. So, every time she went doing the shopping to the market, she asked him a slightly higher sum of money than necessary: in this way, she was able to save some money for surgery in Marrakesh.

I asked her if she hadn’t been a little bit hypocritical in making others pay for her “mistake”, but her answer was no. “It is them who want my virginity, not me. So, they will pay for it”, she said.

What is your family’s opinion about this experience of yours?

I guess they are positive about that, we had no frictions on the issue. I think my family have only one concern: they say that I am so involved in the social sector that I always end up being broke, and that I don’t think enough about myself. They know I am ready to work tirelessly on my projects for women, so they ask me: “When will you think about your own private life? When will you think about yourself and your own future?”.

The public conferences Loubna Bensalah took part into were held on 27th and 28th November 2018, respectively in Milan (at Palazzo Marino) and Turin (at the University of Turin and at the Circolo dei Lettori).

NOTES ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Janiki Cingoli

Janiki Cingoli has dealt with international issues since 1975. Since 1982 he has begun to deal with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, promoting the first occasions in Italy for dialogue between Israelis and Palestinians and in 1989 he founded in Milan the Italian Center for Peace in the Middle East (CIPMO), which has since directed until 2017 when he was elected President.

Read all the EDITORIALS